Revocation of the activity permit of the religious orders in Hungary – and the road to their dissolution (1945–1950)

The communist leaders saw a threat in the religious orders strengthened between the two world wars. For that reason, in 1950, the state withdrew the activity permit of 63 Hungarian religious orders. As a result of this decision eleven and half thousand professions became the victims of events of seventy years ago.

The attack against the religious orders can be considered as a culmination of series of acts of the communist regime against the churches. The requirement of separation of the churches from the state arose already in 1945, however, its realization was not based on negotiations and the search for mutual benefits, but it was executed by steps, within the frame of which the church was, not avoiding openly unilateral and violent means, under constant pressure. The ruling communist party attacked the church openly and covertly with the aim to destroy it, respectively to completely push it out from the life of the society.

The majority of the lands owned by the church, and the religious orders amongst them, was taken from them in 1945. They used to serve before as means for funding the operation of their schools, hospitals and ecclesiastical institutions. Land confiscation without any compensation was approved by the episcopal conference led by the Esztergom bishop József Mindszenty despite the fact that the unfair nature of this step was known to them. The bishops asked for God´s blessing on the new owners of the land estates, but it hasn´t done anything to alter the fact that the churches were deprived of their economic basis.

Subsequently, the pushing out of the churches further continued. In 1946, based on the Decree of the Ministry of Interior Affairs all the associations – the religious associations among them – were dissolved. The dissolution of the civil sphere had an extremely sensitive impact on the Hungarian churches, as a flourishing association life was created in the towns and villages between the two world wars.

However, the suffering did not end with this, as in summer 1948 from the church – deprived of its material goods and social base – also its educational institutions were taken away, that means the schools were nationalized. With this decision the church education with several hundred years of history was abolished in Hungary. The church was represented at every level of education, starting from the kindergartens, through elementary schools, secondary schools and ending with higher education institutions. A lot of male and female religious orders considered education and bringing up children and young people to be their primary task. As a sign of a protest against the nationalization, József Mindszenty did not allow the monks to continue teaching in the educational institutions, thus creating the narrative of the single party state that the monks are useless, as the state has taken over their previous tasks.

It was easier for the single party state to get along with the Protestant churches and the Jewish community. After having replaced the church leadership that did not sympathize with them, at the end of 1948 they agreed upon the relationship between the state and the given ecclesial community. In fact, the state has taken everything from them, but they were given certain benefits for their activities. This direction was not accepted by the catholic chief pastors, and not only because of the unilateral pressure, but also due to the reason that they wanted to solve issues, on behalf of the solution of which the consent of the Holy See would be required. However, the deteriorating political situation made it impossible for the Holly See to take part in the negotiations, and thus the communists decided to take another crucial step: on Christmas Day 1948, the most important archbishop of the Hungarian Catholic Church, the Esztergom bishop József Mindszenty, was detained. The unambiguous purpose of his detention, prosecution and following life imprisonment was his intimidation, but the abandoned episcopal conference did not start the negotiations with the single party state even after the arrest of the cardinal, all the more, that they received a message from Pope Pius XII to stay united and to resist and be resilient.

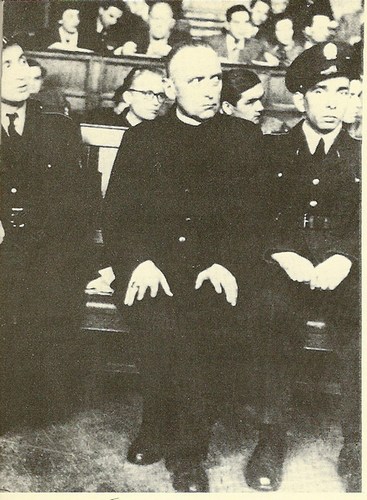

Archbishop József Mindszenty during the show trial in 1949

In the course of 1949, the system of one single party became definite in Hungary and the agreement with the churches came again to the fore. The episcopal conference tried to resist further political pressure towards them, but the state, in order for an agreement to be born, launched an attack by brutal means. The two most important potentials for extortion were the launching of the peace movement of the Catholic clergy (what provoked terror from the division of the church) and the displacement, internment of the monks.

Between June and September 1950, female and male monks were deported in several waves, initially from the western border areas adjoining Austria and from the southern border areas adjoining Yugoslavia, later from other marked places and they were gathered in monasteries in the central part of the country. During the night, they were mugged by the members of the state security and they had only few minutes to collect their necessary things and to board the tarpaulin trucks, which took them away. They even did not respect the older, ill monks, everybody had to leave his or her home hitherto.

The monks did not have any clue where they were taken, an opinion began to prevail in certain groups that perhaps they were taken right to Siberia. They noted with great relief that apparently they got into another monastery, where they were welcomed. The interned female and male monks were placed mixed and the monastery, abbey or the bishop´s palace that welcomed them, was given the task to ensure care for them, what was a huge burden for the „hosts”. In numerous cases there were not enough human resources, but thanks to the active participation of the local civilians living in the neighbourhood, it was possible to take care about the coming monks everywhere. This happened also in case of places like Vác, Esztergom and Máriabesenyő. Approximately 500 nuns were placed in the Cistercian abbey in the town of Zirc and the Cistercian monks had to take care not only about the nuns, but also about themselves.

With internment they wanted the bishops to break eventually and to start negotiations with the state. The tactics have proven to be successful, because the bishop in the town of Kalocsa, József Grősz (due to obstacles on the side of Mindszenty), the President of the Episcopal Conference, visited József Darvas, the Minister for Religious Affairs and Public Education with the requirement to sort the issue of the interned monks somehow. Mátyás Rákosi, the leader of the single party state (Magyar Dolgozók Pártja- Hungarian Workers Party, note of translator) has made it clear that the situation of the monks could not be resolved separately, but only as a part of a complex agreement. With this the bishops were forced to sit down at the negotiating table, as they did not want to threaten the fates of more than ten thousand monks. Finally, the power superiority of the single party state has prevailed in the negotiations in every aspect and on the 30th August 1950 the agreement enforced by the Communists was signed.

A few days after the agreement was signed, on the 7th September, the activity permit of the religious orders was revoked, nearly 12,000 monks were deprived of their current way of life. Exemption was given only to four orders, also because of the reason to demonstrate outwards the freedom of religious beliefs enshrined in the Constitution. The state played key role in the selection of these four orders. During the negotiations they clearly proclaimed that it was necessary to drastically reduce the number of the monks. It was generally known that due to alleged or real concerns of the power the Jesuits, the Cistercians and the Premonstratensians certainly could not get operating permission and it was also clear from the decree from the 7th September that the Benedictines, the Piarists, the Franciscans and the school nuns from Szeged were entitled to provide their activities in Hungary only within severe frames (60 monks in every order) and they were entitled to – as an educational order – operate two-two secondary grammar schools.

There was no church school in operation in Hungary between 1948 and 1950, in the fall of 1950 it was possible to start education in eight returned church high schools: in the towns of Pannonhalma and Győr (Benedictines), in Budapest (Piarists and school nuns), in the town of Kecskemét (Piarists), in Szentendre (Franciscans), in Esztergom (Franciscans) and in the town of Debrecen (school nuns). From these institutions – of course, without any support from the state, they managed their operation from own sources – have grown the protective bastions of the catholic future.

The monks, who were forced to spread, had to look for new home, work – nobody could be unemployed in the communist Hungary – and they had to stand their ground in the situation that was diametrically different from their current way of life. Some of the male monks – to the extent determined by the state – were taken over by the dioceses, later they worked as bell ringers, sacristans and catechists at the parish. The ones who did not make it to get under the management of the individual dioceses, had to work manually and they found work in various factories and production units. One of the results of revocation of the activity permit was that the state forbade meeting of the people who used to belong to one community, they were forbidden also to keep contacts. If they violated this ban, it was considered as anti-state organization and it was also punished accordingly – most often they were prosecuted and they were sentenced to prison.

Despite the dissolution, neither the fundamental, ideological dictatorship of the single party state was able to destroy all what the monks had sworn long before. Whether they have worked in a garment factory, as radio repairmen or as teachers, in every situation in life they have found a way – not without danger at all – how to convey the Christian values of the Gospel.

The monks were persecuted by the state security until the regimes change, operative records were taken about individual orders and their members, the vast majority of which was – unfortunately – destroyed in 1989. During the whole time the single party state was enemy to the religious orders and in the interest of performing the current church policy it exercised control over them or it opposed them sometimes in a more active and sometimes in a more passive way.

As to the increase in the numbers of the monks or establishment of a church school, this was not possible until 1989.

This text was written by hungarian historians Bernadett Diera Wirthné and Attila Viktor Soós

Ústav pamäti národa

Miletičova 19

P. O. Box 29

820 18 Bratislava 218

© Ústav pamäti národa 2020 – 2024, všetky práva vyhradené | Vyhlásenie o prístupnosti | Mapa stránky